The Art of Buying a Dollar for 50 Cents: What is Value Investing?

A Simple Analogy: Finding Bargains in the Stock Market

At its heart, value investing is an approach to the stock market that mirrors a familiar real-world activity: bargain hunting. Imagine finding a high-quality, brand-name item on a clearance rack, not because it’s defective, but because the store is overstocked or the item is temporarily out of fashion. A savvy shopper recognizes the item’s true, lasting worth and buys it at a significant discount, confident in the value they are receiving. Value investing applies this same logic to the stock market. It is not about buying “cheap” stocks from struggling companies; it is the art of buying shares in solid, well-run businesses that are temporarily trading for less than their real worth. The foundational idea is that if an investor consistently buys what they determine to be one dollar’s worth of a business for fifty cents, they will methodically build wealth over the long term.

Beyond the Hype: The Core Philosophy of Intrinsic Value

Value investing is an investment paradigm that involves purchasing securities that appear underpriced according to some form of fundamental analysis. The central belief underpinning this strategy is that the stock market is not always rational. Due to short-term factors, such as disappointing quarterly profits, negative news cycles, or widespread economic panic, the market can be driven by emotion. This collective fear or greed can cause a company’s stock price to detach from its underlying, long-term reality.

This reality is what value investors call a company’s “intrinsic value.” While it is not an exact science, estimating this intrinsic value is the primary task of the value investor. It involves a deep dive into a company’s financial health by studying its financial statements (assets, earnings, cash flows) and assessing its qualitative strengths, such as its competitive position and management quality, to arrive at an estimate of the business’s true worth. The goal is to find stocks trading at a significant discount to this calculated value, creating what is known as a margin of safety.

The Two Pillars: “Price is What You Pay, Value is What You Get”

This famous maxim, popularized by legendary investor Warren Buffett, who learned it from his mentor Benjamin Graham, perfectly encapsulates the core distinction that value investors make. “Price” is the figure you see quoted on a screen every day; it is the amount of money required to buy one share of a stock at any given moment. This price is often volatile, influenced by the market’s daily moods and the transactions of a small fraction of shareholders.

“Value,” on the other hand, is the underlying worth of the business itself. It is independent of the daily stock quote and is rooted in the company’s real assets, its capacity to generate earnings, and its future prospects. A value investor understands that a company’s stock price can fluctuate dramatically without any material change in its intrinsic value. For instance, a temporary profit disappointment might cause shareholders to panic and sell, driving the price down. A value investor recognizes that for most long-term businesses, the real effect of a short-term profit dip on the company’s long-term value is often small. This disconnect between the volatile market price and the more stable intrinsic value is precisely where the value investor finds opportunity.

Why Patience is Your Greatest Asset: A Long-Term Perspective

Value investing is fundamentally a long-term strategy. It stands in stark contrast to momentum investing, which bets that recent price trends will continue in the short term, often fueled by “fear of missing out” (FOMO). A value investor buys a stock not because it is popular or rising, but because it is undervalued. The expectation is that, over time, the market will eventually recognize the company’s true worth and “correct” its price upwards. This process does not happen overnight; it can take months or even years.

This long-term horizon demands a specific temperament. The path of a value investor is often lonely and psychologically arduous. There can be extended periods, sometimes lasting for several years, during which a value-oriented portfolio underperforms the broader market. During these times, value investors may be dismissed as out of touch or foolish. To succeed, one must possess the fortitude to stick with their analysis and the patience to wait for their investment thesis to play out, ignoring the siren song of short-term market trends.

The discipline is not just about financial analysis, but about mastering one’s own psychology. The market’s mispricings are often a direct result of the collective emotional reactions of other investors, their fear during downturns, and their greed during bubbles. The value investor’s edge comes from their ability to remain dispassionate and objective, exploiting the irrational behavior of others. This is not merely a financial strategy; it is a form of behavioral arbitrage. The “value” is found in the gap between a company’s fundamentally-driven intrinsic worth and its emotionally-driven market price. For the novice, this understanding is empowering: success in value investing hinges as much on emotional discipline and a rational temperament as it does on financial acumen.

The Unshakeable Foundation: Core Principles of the Value Investor

Principle 1: The Margin of Safety – Your Ultimate Protection

Warren Buffett has called the “margin of safety” the three most important words in investing. This principle, first articulated by Benjamin Graham, is the bedrock of the value investing philosophy. The margin of safety is the difference between the estimated intrinsic value of a stock and the price at which it is purchased. If an investor calculates a stock’s intrinsic value to be $100 per share and buys it for $65, their margin of safety is $35, or 35%.

The purpose of this buffer is to protect the investor from the inevitable uncertainties of the future. It provides a cushion against human error in analysis, plain bad luck, or the extreme volatility that can strike markets without warning. Valuation is an imprecise art, not a hard science; even the most thorough analysis involves making assumptions about the future, which is inherently unpredictable. A large margin of safety means that even if the future is not as bright as anticipated, or if the initial valuation was overly optimistic, there is a lower probability of suffering a significant loss. Buffett has used a bridge-building analogy to explain the concept: if you need to drive a 10,000-pound truck across a bridge, you build the bridge to handle 30,000 pounds. That extra capacity is the margin of safety.

Principle 2: Meet Mr. Market, Your Manic-Depressive Business Partner

To help investors navigate the psychological pressures of market fluctuations, Benjamin Graham created the allegory of “Mr. Market” in his book The Intelligent Investor. He asks the investor to imagine being in business with a partner named Mr. Market. Every day, this partner shows up and offers to either buy the investor’s shares or sell his own shares at a specific price.

The crucial detail is that Mr. Market is a manic-depressive. On some days, he is euphoric, seeing only a rosy future for the business, and offers a ridiculously high price. On other days, he is overcome with pessimism and despair, offering to sell his shares at a foolishly low price. The intelligent investor is free to transact with him at these extreme prices, selling when he is euphoric and buying when he is despondent, but is equally free to ignore him completely the rest of the time. The lesson is profound: the investor should never let Mr. Market’s daily mood dictate their own assessment of the business’s value. The market’s price is there to serve the investor, not to guide them. This parable transforms the abstract and often intimidating concept of market volatility into a tangible, manageable relationship, empowering the investor to profit from market folly rather than participate in it.

Principle 3: You’re a Business Owner, Not a Stock Trader

A core tenet shared by both Graham and Buffett is that an investor should always think of themselves as a business owner, not merely a holder of a stock certificate. This perspective fundamentally changes the approach to investing. Instead of focusing on short-term price movements and market trends, the focus shifts to the long-term health and operational performance of the underlying company.

This means conducting thorough due diligence as if one were purchasing the entire business. An investor must understand how the company makes money, its competitive advantages, the quality of its management, and its long-term financial prospects. This business-like approach requires ignoring market noise and stock price fluctuations 99% of the time. The only moments the market price truly matters are on the day of purchase and the day of sale. In between, the investor’s attention should be fixed on the company’s fundamental performance. As long as the business remains strong, temporary dips in the stock price are not a cause for concern but potential opportunities to acquire more of a good business at a better price.

Principle 4: The Contrarian Mindset – Profiting from Fear and Greed

Value investing is inherently a contrarian activity. It requires psychological strength to go against the prevailing market sentiment. As Warren Buffett famously advised, an investor should be “fearful when others are greedy, and greedy when others are fearful”.

This principle is the practical application of capitalizing on the market’s emotional swings. When negative news or an economic downturn causes widespread panic, emotional investors tend to sell indiscriminately, pushing the prices of even excellent companies to undervalued levels. This is when the value investor, armed with their dispassionate analysis, steps in to buy. Conversely, during periods of excessive optimism and market euphoria, when stock prices are driven by hype rather than substance, the value investor remains on the sidelines, avoiding the temptation to chase overvalued assets. This requires a mindset comfortable with not following the herd, buying when peers are selling, and selling when everyone else is buying.

The Architects of an Enduring Strategy: From Graham to Buffett

Benjamin Graham: The Father of Value Investing

The discipline of value investing was born in the 1920s at Columbia Business School, developed by finance professor Benjamin Graham, who is universally regarded as its father. Traumatized by the financial ruin his family experienced after the Panic of 1907 and his own substantial losses in the 1929 crash, Graham sought to transform investing from a speculative gamble into a rational, disciplined profession. He codified his philosophy in two foundational texts,

Security Analysis (1934) and The Intelligent Investor (1949), which remain essential reading for investors today.

Graham made a crucial distinction between two types of investors: the “defensive” and the “enterprising”. The defensive investor is one who seeks, above all, “freedom from effort, annoyance, and the need for making frequent decisions”. Their primary goal is the avoidance of serious mistakes or losses. For this type of investor, Graham prescribed a simple, disciplined approach based on a diversified portfolio of large, prominent, and conservatively financed companies. The enterprising investor, in contrast, is willing to devote significant time and effort to research in pursuit of exceptional returns.

To guide the defensive investor, Graham laid out a set of strict, quantifiable criteria for stock selection. These rules were designed to identify financially sound companies trading at bargain prices, providing a built-in margin of safety. His key benchmarks included.

- Adequate Company Size: To avoid the volatility of smaller companies, he focused on large, established enterprises.

- Strong Financial Condition: He required a current ratio (current assets divided by current liabilities) of at least 1.5 and stipulated that total debt should not be more than 110% of current assets for industrial companies.

- Earnings Stability: A company must have shown positive earnings for each of the past ten years.

- Consistent Dividends: An uninterrupted history of dividend payments for at least the past 20 years was a sign of financial stability.

- Moderate Price-to-Earnings (P/E) Ratio: The current stock price should not be more than 15 times the average earnings of the past three years.

- Moderate Price-to-Book (P/B) Ratio: The current price should not exceed 1.5 times the last reported book value.

- Combined Rule: As a final check, the product of the P/E ratio and the P/B ratio should not exceed 22.5 (15×1.5=22.5).

Warren Buffett: The Evolution to “Wonderful Companies”

Warren Buffett, Graham’s most celebrated student, began his career as a strict adherent to his mentor’s teachings. He excelled at what he later termed “cigar butt” investing: searching for mediocre businesses that were trading at such a low price that there was one last, free “puff” of profit left in them. This approach involved buying companies for less than their net working capital, a classic Graham-style bargain.

However, Buffett’s philosophy underwent a profound evolution, largely due to the influence of his long-time partner, Charlie Munger. Munger convinced Buffett that it was far better to buy a “wonderful company at a fair price” than a “fair company at a wonderful price”. This marked a pivotal shift in the practice of value investing. The focus moved from a purely quantitative assessment of cheapness based on balance sheet assets to a more qualitative assessment of a business’s long-term quality and competitive strength.

This evolution led to Buffett’s focus on the concept of an “economic moat”. An economic moat is a durable competitive advantage that protects a company’s profits from competitors, much like a medieval castle’s moat protected it from invaders. These moats can come in several forms: a powerful brand with pricing power (like Coca-Cola), a network effect where the service becomes more valuable as more people use it (like American Express), a low-cost production advantage, or high switching costs for customers. This new framework allowed Buffett to invest in high-quality, growing businesses and hold them for the long term, a departure from Graham’s strategy of selling a stock once it reached its calculated fair value.

This philosophical shift was not just an intellectual exercise; it was a necessary adaptation to a changing economic world. Benjamin Graham’s framework was forged in the fires of the Great Depression, a time when corporate survival was not guaranteed and the most reliable measure of value was a company’s tangible, liquidatable assets. His rules were defensive, designed to protect capital above all else. In contrast, Warren Buffett was operating in the prosperous post-World War II era, which saw the rise of powerful global brands and a burgeoning consumer economy.

His 1972 investment in See’s Candies was a watershed moment. He paid a price three times the company’s book value, a clear violation of Graham’s rules, because he recognized that its most valuable asset was not on the balance sheet. It was the intangible power of the See’s brand that commanded intense customer loyalty and allowed the company to consistently raise prices. This shift from an industrial economy, where tangible assets were paramount, to a consumer- and service-based economy, where intangible assets like brands and intellectual property drive value, necessitated an evolution in the application of value investing principles. It demonstrates that value investing is not a rigid dogma but a dynamic philosophy that must adapt to the economic realities of its time.

The Value Investor’s Toolkit: Mastering the Best Valuation Methods

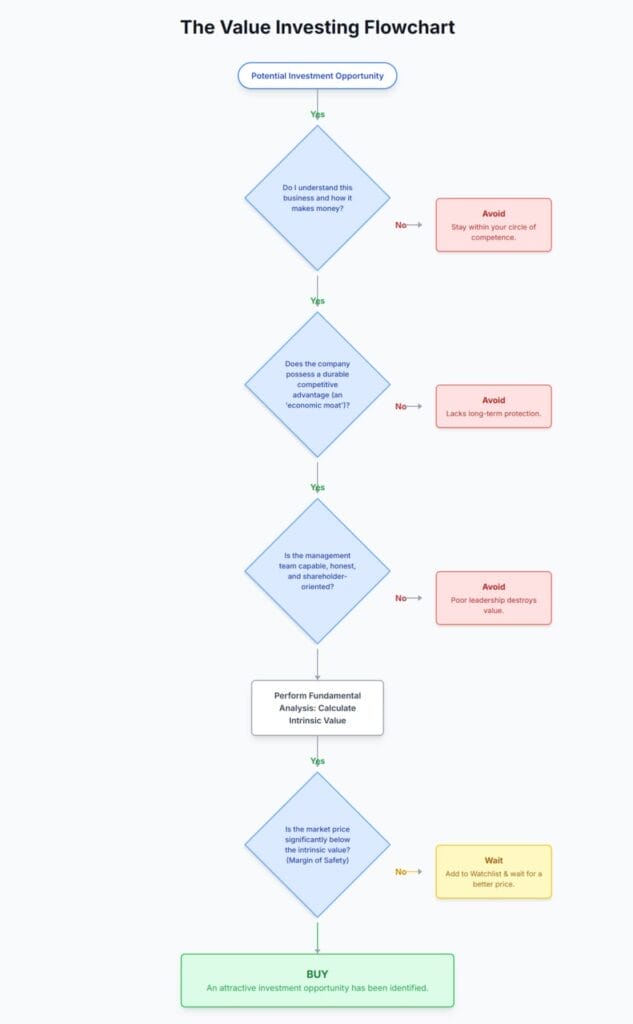

To apply the principles of value investing, an investor needs a toolkit of methods to estimate a company’s intrinsic value. These tools can be broadly categorized into two groups: quick assessment ratios, which act as initial screening devices to identify potentially interesting stocks, and more in-depth intrinsic value models, which provide a more comprehensive valuation.

The Quick Assessment – Key Financial Ratios

Financial ratios are powerful tools for quickly comparing a company’s stock price to a key measure of its financial health or performance. They help standardize companies of different sizes and are used to screen for stocks that may be trading at a discount to their peers or their own historical averages.

Price-to-Earnings (P/E) Ratio: Are You Paying a Fair Price for Profits?

The Price-to-Earnings (P/E) ratio is one of the most widely used valuation metrics. It compares a company’s current stock price to its earnings per share (EPS) over the past twelve months.

- Formula: P/E Ratio=Earnings Per Share (EPS)Market Value Per Share

- Interpretation: The P/E ratio tells an investor how much they are paying for each dollar of a company’s earnings. A low P/E ratio can indicate that a stock is undervalued, while a high P/E ratio suggests that investors have high expectations for future growth.

- How to Use: The P/E ratio is most useful when comparing a company to its own historical P/E range and to the average P/E of its industry peers. It is also important to distinguish between the trailing P/E, which uses past earnings, and the forward P/E, which uses analysts’ future earnings estimates.

- Caveats: The P/E ratio is meaningless for companies with negative earnings and can be misleading when comparing companies in different industries, as average P/E ratios vary significantly by sector.

Price-to-Book (P/B) Ratio: Comparing Price to a Company’s Net Assets

The Price-to-Book (P/B) ratio compares a company’s market capitalization to its book value. Book value is a company’s total assets minus its total liabilities, representing the net asset value of the company.

- Formula: P/B Ratio=Book Value per ShareMarket Price per Share

- Interpretation: This ratio shows how much investors are willing to pay for each dollar of a company’s net assets. For traditional value investors, a P/B ratio under 1.0 is a strong signal that the stock may be undervalued, as it means the company could theoretically be liquidated for more than its stock market value.

- How to Use: The P/B ratio is particularly useful for valuing companies in asset-heavy industries such as banking, insurance, and manufacturing, where book value is a more stable and meaningful measure of worth.

- Caveats: This ratio is less effective for service-based or technology companies, whose primary assets are intangible (like intellectual property or brand value) and are not fully captured on the balance sheet.

Enterprise Value to EBITDA (EV/EBITDA): A More Holistic View

The EV/EBITDA multiple is often favored by professional analysts because it provides a more comprehensive valuation picture than the P/E ratio. It compares a company’s total value, including its debt, to its earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization.

- Formula: EV/EBITDA=EBITDAEnterprise Value

- Where Enterprise Value (EV) = Market Capitalization + Total Debt – Cash and Cash Equivalents.

- Interpretation: This ratio shows how many years of EBITDA it would take to pay for the entire company. A lower EV/EBITDA multiple suggests a company might be undervalued.

- How to Use: Because it is capital structure-neutral (it includes debt) and ignores differing tax policies, EV/EBITDA is an excellent tool for comparing companies with different levels of leverage or those in different countries. It is also commonly used in merger and acquisition analysis.

- Caveats: A key limitation is that EBITDA can overstate a company’s cash flow because it does not account for changes in working capital or necessary capital expenditures (CapEx) to maintain the business.

Calculating True Worth – Intrinsic Value Models

While ratios provide a quick snapshot, intrinsic value models attempt to calculate a more precise estimate of a company’s worth based on its ability to generate cash in the future.

The Gold Standard: A Step-by-Step Guide to Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Analysis

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) analysis is a valuation method based on the principle that the value of a business is the sum of all its expected future cash flows, discounted back to their value in today’s money. This method is grounded in the fundamental concept of the “time value of money”, a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow because it can be invested to earn a return.

- Simplified Step-by-Step Process:

- Forecast Free Cash Flow (FCF): Project the company’s unlevered free cash flow (the cash available to all investors, both debt and equity holders) over a specific forecast period, typically 5 to 10 years. This requires making assumptions about revenue growth, profit margins, and capital expenditures.

- Calculate the Terminal Value: Since a business is expected to operate indefinitely, a “terminal value” must be calculated to represent the value of all cash flows beyond the initial forecast period. This is often done using either a perpetual growth model or an exit multiple method.

- Determine the Discount Rate: A discount rate is chosen to convert future cash flows into their present value. The most common rate used is the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC), which represents the blended cost of a company’s debt and equity financing and reflects the overall risk of the investment.

- Discount the Cash Flows: Each year’s projected FCF and the terminal value are discounted back to the present using the WACC. The sum of these discounted values gives the company’s Enterprise Value.

- Calculate Equity Value: To find the intrinsic value for shareholders (the Equity Value), subtract the company’s net debt (total debt minus cash) from the Enterprise Value.

- Pros and Cons: DCF is considered one of the most theoretically sound valuation methods because it is based on a company’s ability to generate cash. However, its main drawback is its extreme sensitivity to the assumptions used for growth rates and the discount rate. Small changes in these inputs can lead to vastly different valuation outcomes.

For the Dividend Lover: The Dividend Discount Model (DDM)

The Dividend Discount Model (DDM) is a simpler valuation method that posits a stock’s value is equal to the present value of all its future dividend payments.

- Gordon Growth Model (Constant Growth): The most common version of the DDM is the Gordon Growth Model, which assumes dividends will grow at a constant rate (g) forever.

- Formula: Price (P)=r−gD1

- Where D1 is the expected dividend in the next period, r is the required rate of return (or cost of equity), and g is the constant dividend growth rate.

- Formula: Price (P)=r−gD1

- Ideal Use: This model is best suited for valuing mature, stable companies with a long history of paying predictable and steadily growing dividends, such as blue-chip companies or utilities.

- Limitations: The DDM is not applicable to companies that do not pay dividends (such as many growth and tech stocks). Like the DCF, it is also highly sensitive to its inputs, and the model becomes invalid if the assumed growth rate (g) is higher than the required rate of return (r).

The Original Formula: Calculating the Graham Number

Benjamin Graham developed a simple formula to estimate the maximum price a defensive investor should pay for a stock, providing a quick check for undervaluation based on his core principles.

- Formula: Graham Number=22.5×(Earnings Per Share)×(Book Value Per Share)

- Interpretation: The number 22.5 is derived from Graham’s criteria that the P/E ratio should not exceed 15 and the P/B ratio should not exceed 1.5 (15×1.5=22.5). If a stock’s current market price is below its calculated Graham Number, it is considered a potentially undervalued security according to his framework.

- Usefulness: This formula provides a straightforward, conservative upper limit for a stock’s price, blending both earnings and asset value into a single metric. However, it shares the limitations of its underlying components, particularly the P/B ratio’s inadequacy for asset-light businesses.

Value Investing in Action: Timeless Case Studies of Success

Theory and formulas are essential, but the true power of value investing is best understood through real-world application. The following case studies of investments made by Warren Buffett illustrate how the principles of value investing can lead to extraordinary long-term success.

Case Study 1: Warren Buffett & Coca-Cola (1988) – Buying a Global Empire During a Market Crash

The Context: In October 1987, the stock market experienced a dramatic crash known as “Black Monday,” which created an environment of widespread fear and panic selling. In the aftermath, the stock prices of many excellent companies were depressed, sold off with little regard for their underlying business fundamentals.

The Opportunity: While many investors were fleeing the market, Warren Buffett was searching for opportunities. He invested over $1 billion in The Coca-Cola Company between 1988 and 1989. He recognized that the market’s short-term panic had no bearing on Coca-Cola’s long-term business reality. The company possessed one of the most powerful economic moats in the world: its globally recognized brand. People around the world would continue to drink Coke regardless of the stock market’s mood. Buffett saw a “perfect business” with consistent growth, a massive international runway, and shareholder-friendly management, all available at a reasonable price due to the market’s overreaction.

The Lesson: This investment is a quintessential example of Buffett’s famous advice to be “greedy when others are fearful.” It demonstrates the importance of separating a company’s business performance from its stock price performance. The market crash provided a rare chance to buy a wonderful company at a good, not necessarily dirt-cheap, price. The long-term results speak for themselves: a $1,000 investment in Coca-Cola at the time Buffett began buying would have grown to over $36,000 by 2025, a testament to the power of buying quality and holding for the long term.

Case Study 2: Warren Buffett & American Express (1963) – Finding Opportunity in the “Salad Oil Scandal”

The Context: In 1963, American Express was embroiled in a massive scandal. A subsidiary had issued warehouse receipts for millions of pounds of salad oil to a company called Allied Crude Vegetable Oil. It was later discovered that the tanks were mostly filled with water, and the oil was a fiction. When Allied defaulted, American Express was on the hook for enormous losses, and the market panicked, fearing the company would go bankrupt. The stock price collapsed by more than 50%.

The Opportunity: This was a classic “Mr. Market” moment. The market was in a state of “pitiful gloom”, convinced that American Express was doomed. Instead of panicking, a young Warren Buffett did his own on-the-ground research. He went to restaurants and banks, observing that customers and merchants were still using American Express traveler’s checks and credit cards without hesitation. He concluded that the scandal, while costly, had not damaged the company’s core business or its powerful brand; its economic moat was intact. Trust in the American Express franchise remained strong. Seeing a great business at a foolishly low price, Buffett invested 40% of his partnership’s capital, amassing a 5% stake in the company.

The Lesson: This case study teaches investors to look past the headlines and analyze the true, long-term impact of negative news. Often, the market overreacts to scandals or setbacks, creating incredible buying opportunities in high-quality companies for those who do the work to understand the underlying business reality. The stock recovered, and the investment proved enormously profitable for Buffett’s partners.

Case Study 3: Warren Buffett & See’s Candies (1972) – The Sweet Lesson of Pricing Power and Quality

The Context: The purchase of See’s Candies for $25 million in 1972 was a landmark deal that signaled Buffett’s evolution from the strict, asset-based value investing of Benjamin Graham to his modern approach of buying high-quality businesses. At three times its book value, the price would have been unthinkable for a classic Graham investor.

The Opportunity: Buffett and his partner, Charlie Munger, recognized that See’s most valuable asset was not its factories or inventory, but its powerful, intangible brand and the resulting customer loyalty. They understood that See’s had immense “pricing power”, the ability to raise its prices year after year without losing customers, who associated the brand with quality and nostalgia. This meant the business could generate ever-increasing profits with very little need for additional capital investment. It was a cash-generating machine.

The Lesson: See’s Candies taught Buffett that the best businesses are often those with intangible assets that don’t appear on a balance sheet. It cemented the shift in his philosophy from buying “fair companies at a wonderful price” to buying “wonderful companies at a fair price.” The investment has been a spectacular success, generating over $2 billion in pre-tax income for Berkshire Hathaway on an initial investment of just $25 million. It proves that paying a seemingly high price for a truly exceptional business with a durable competitive advantage can be far more lucrative than buying a mediocre business at a statistical bargain.

Value Investing in the 21st Century: Navigating a Modern Market

The Great Debate: Is Value Investing Still Relevant Today?

In the past decade, a period dominated by the meteoric rise of technology and growth stocks, many have questioned the relevance of value investing. From roughly 2009 to 2020, growth strategies significantly outperformed value, leading some pundits to declare the old-school approach “dead”. This underperformance has been a source of frustration for value-oriented investors, testing their patience and conviction.

However, a broader historical perspective tells a different story. Research by Nobel laureates Eugene Fama and Kenneth French has shown that over very long time horizons, value stocks have historically outperformed growth stocks. From 1927 through 2019, value outperformed growth in 93% of rolling 15-year periods. This suggests that the recent dominance of growth may be a cyclical phenomenon rather than a permanent paradigm shift. Indeed, market dynamics have begun to shift. In 2025, value stocks have shown strong performance, particularly in international markets, reminding investors of the strategy’s resilience. Value investing has historically performed well during periods of economic uncertainty, high inflation, and rising interest rates, as investors pivot toward companies with stable earnings and strong balance sheets. Therefore, reports of its demise appear to be premature; value investing remains a relevant and powerful strategy, especially for investors focused on capital preservation and long-term wealth creation.

The Tech Challenge: Valuing Intangible Assets

The most significant challenge for value investing in the 21st century is adapting its traditional valuation methods to a tech-driven economy. Classic valuation metrics like the Price-to-Book (P/B) ratio were developed for an industrial economy where a company’s worth was tied to its tangible assets: factories, machinery, and inventory. Today, many of the world’s most valuable companies are in the technology sector, and their primary assets are intangible: software code, patents, user data, network effects, and brand recognition. These assets are either absent from the balance sheet or significantly understated, rendering the traditional P/B ratio far less meaningful.

This challenge necessitates a continued evolution of the value investing philosophy, much like the shift from Graham to Buffett. The definition of “value” and “assets” must expand. Modern value investors are developing new frameworks to account for intangible capital. For example, some research suggests that capitalizing research and development (R&D) expenses as an asset rather than an expense provides a more accurate picture of a tech company’s value. One study found that adjusting book value to include intangible assets vastly improves the historical returns of a value-based strategy, particularly since the financial crisis.

Contemporary value investors like Bill Nygren argue that the principles are timeless, but the application must adapt. They contend that a company with a high P/E ratio, like Google or Apple, can still be a “value” stock if its powerful intangible assets and growth prospects mean its intrinsic value is far higher than its current price. The challenge is not that value investing is broken, but that investors must move beyond outdated, purely quantitative screens and embrace a more holistic analysis that recognizes the immense value of intangible moats in the modern economy.

Value vs. Growth vs. Index Funds: Choosing the Right Path for You

For a new investor, understanding the distinctions between the primary equity investing strategies is crucial for building a portfolio that aligns with their goals, risk tolerance, and level of desired involvement. The three main approaches are value investing, growth investing, and index investing.

- Value Investing: As detailed throughout this guide, value investors are like bargain hunters. They seek to buy stocks for less than their intrinsic worth. These are often established, mature companies that may be temporarily out of favor. They typically have lower P/E ratios and often pay dividends. The primary risk is the “value trap”, a stock that is cheap for a good reason and never recovers.

- Growth Investing: Growth investors are focused on the future. They seek companies with the potential to grow their earnings and revenue at a much faster rate than the overall market. These are often innovative companies in sectors like technology. They tend to have high P/E ratios and rarely pay dividends, as they reinvest all profits back into the business to fuel further expansion. The primary risk is that these high expectations are not met, which can cause the stock price to fall dramatically.

- Index Investing: This is a passive strategy that aims to match the performance of a major market index, such as the S&P 500, rather than beat it. An index fund or ETF simply buys and holds all the stocks in the benchmark index it tracks. This approach offers instant diversification, extremely low costs, and is very low-maintenance. The primary risk is market risk; if the overall market goes down, the index fund will go down with it, as there is no active manager to take defensive measures.

| Feature | Value Investing | Growth Investing | Index Investing |

| Goal | Buy stocks for less than their intrinsic value; wait for the market to recognize their true worth. | Identify companies with high potential for above-average earnings and revenue growth. | Match the performance of a specific market index (e.g., S&P 500) at a very low cost. |

| Typical Company Profile | Mature, well-established companies, possibly in out-of-favor industries. Often pay dividends. | Younger, innovative companies in rapidly expanding sectors (e.g., technology). Rarely pay dividends. | A broad basket of companies representing the entire index (e.g., the 500 largest U.S. companies). |

| Key Metrics | Low P/E Ratio, Low P/B Ratio, High Dividend Yield, Strong Free Cash Flow. | High Revenue Growth Rate, High EPS Growth, High P/E Ratio, Strong Market Position. | Tracking Error (how closely it follows the index), Expense Ratio. |

| Risk Level | Moderate. Risk of “value traps” (cheap stocks that stay cheap) and long periods of underperformance. | High. Risk that high growth expectations are not met, leading to significant price drops. High volatility. | Market Risk. The fund will decline with the overall market. No protection against downturns. |

| Cost & Effort | High. Requires significant research, analysis, patience, and emotional discipline. | High. Requires research to identify future trends and winners, and tolerance for volatility. | Very Low. A passive, “set it and forget it” strategy with minimal effort and very low fees. |

The Future of Value: How AI and Big Data are Reshaping Analysis

The evolution of value investing continues into the 21st century with the advent of powerful new technologies. The next frontier is “quantitative” or “systematic” value investing, which leverages artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, and big data to enhance the investment process. These technologies can systematically screen thousands of companies across dozens of financial metrics, economic data points, and even unstructured data (like news sentiment or product reviews) to identify potential value opportunities far more efficiently than a human analyst ever could.

For example, AI models can be trained on decades of historical data to learn the patterns that have historically identified undervalued companies that went on to outperform. This approach seeks to augment human intelligence, not replace it, by providing a more powerful and data-driven foundation for investment decisions. While the core principles of buying assets for less than their intrinsic value remain unchanged, the tools for identifying those opportunities are becoming exponentially more sophisticated.

Your Path to Becoming a Value Investor

A Beginner’s Action Plan: First Steps and Key Resources

Embarking on the path of a value investor is a journey of continuous learning and disciplined practice. For those just starting out, the following steps provide a clear action plan:

- Build Your Foundation with the Classics: The single most important first step is to read Benjamin Graham’s The Intelligent Investor. This book lays out the entire philosophical and psychological framework of value investing, including the foundational concepts of Mr. Market and the margin of safety.

- Start Within Your “Circle of Competence”: As Warren Buffett advises, invest only in companies and industries you can genuinely understand. If you work in the retail industry, start by analyzing retail companies. If you are passionate about consumer goods, begin there. This approach gives you a natural edge in evaluating a business’s competitive landscape and long-term prospects.

- Practice Without Risk: Before committing real capital, open a paper trading account. This allows you to practice the process of analyzing companies, calculating intrinsic value, and making investment decisions without the risk of financial loss. It is an invaluable way to learn from mistakes and build confidence.

- Cultivate the Right Temperament: Recognize that successful value investing is more about character than intellect. Focus on developing the key psychological traits: patience to hold investments for the long term, discipline to stick to your criteria, and the emotional control to act rationally when the market is panicking or euphoric.

Avoiding the “Value Trap”: How to Tell a Bargain from a Bust

One of the greatest risks for a value investor is the “value trap.” This is a stock that appears statistically cheap, with a low P/E or P/B ratio, but is actually cheap for a very good reason: its underlying business is in a state of irreversible decline. The low price is not an opportunity but a warning sign of a failing company.

To distinguish a true bargain from a value trap, an investor must look beyond the simple numbers and ask deeper, qualitative questions:

- Is the problem temporary or permanent? Is the company facing a short-term headwind (like a product recall or a cyclical downturn) that it can recover from, or is it facing a permanent structural shift (like a new technology that makes its core product obsolete)?

- Is management competent and proactive? A cheap stock with a strong management team that recognizes the problems and has a credible plan to fix them is far more attractive than one with a leadership team in denial.

- Is the entire industry in decline? A cheap company in a dying industry is unlikely to recover. It is often better to find a great company in a good industry that has hit a temporary speed bump.

The Final Word: The Enduring Power of a Disciplined Mind

Ultimately, value investing is more than a collection of formulas and financial ratios; it is a comprehensive philosophy. It is a business-like approach to the stock market that provides a rational framework for making decisions amidst the chaos and emotion of financial markets.

For over a century, from the industrial age of Benjamin Graham to the digital age of today, this strategy has proven its resilience and its ability to create extraordinary wealth. Its success does not depend on predicting the market’s next move or having access to secret information. It depends on a simple, yet powerful, combination of diligent analysis, unwavering patience, and the emotional discipline to buy good businesses when they are on sale. For the investor willing to cultivate this mindset, value investing remains the most intelligent and time-tested path to long-term financial success.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational and educational purposes only and should not be considered financial advice. Investing in financial markets involves risk, including the possible loss of principal. Always conduct your own research and consider consulting with a qualified financial advisor before making any investment decisions.

This website may utilize artificial intelligence to assist in the creation of content. This may include generating ideas, drafting sections, and aiding in the editing process. All content is reviewed and edited by us to ensure accuracy and quality.